What does the Pogues’ Christmas song “Fairytale of New York” have to do with Lolita? The trail links at oblique angles but leads to a story of betrayal, obscenity, and revenge that would have pleased Nabokov, if only he had lived to hear it.

The Irish band’s 1987 carol for the Grinchiest among us tells of a pair of fresh-faced lovers ground down by the Big Apple and reduced to Edward Albee-style fury. The vituperation begins with “you’re a bum, you’re a punk / you’re an old slut on junk” and goes downhill from there.

Jem Finer of the Pogues took the title from the book he was reading when he co-wrote the song: the novel A Fairytale of New York by J.P. Donleavy. Donleavy—like Nabokov—was long notorious for his taboo content and sexual themes. In Donleavy’s Fairytale, a man returning to New York with his wife’s corpse meets up with a woman whose millionaire husband has also just died. Donleavy told the BBC that he likes the song but on hearing it “realised straight away that it didn’t really have anything to do with my book.”

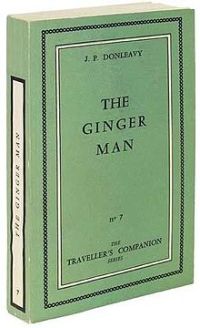

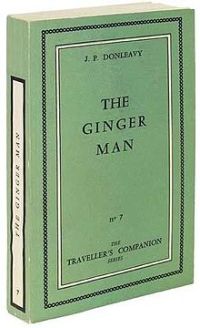

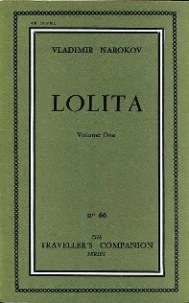

How does “Fairytale” connect with Nabokov? Donleavy leapt to prominence with The Ginger Man in 1955, the year Lolita was published. Nabokov invented a story of a European immigrant’s sexual depravity in America; Donleavy wrote of an American’s sexual adventures in Europe. Both authors steamrolled postwar obscenity standards and found their books’ distribution hamstrung by censorship. Both nevertheless went on to sell tens of millions of copies (The Ginger Man only slightly less than Lolita).

How does “Fairytale” connect with Nabokov? Donleavy leapt to prominence with The Ginger Man in 1955, the year Lolita was published. Nabokov invented a story of a European immigrant’s sexual depravity in America; Donleavy wrote of an American’s sexual adventures in Europe. Both authors steamrolled postwar obscenity standards and found their books’ distribution hamstrung by censorship. Both nevertheless went on to sell tens of millions of copies (The Ginger Man only slightly less than Lolita).

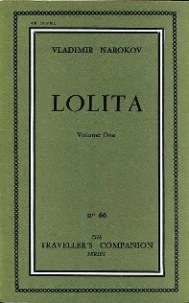

Most importantly, both novels made their debut with Olympia Press, the Parisian publishing house run by Maurice Girodias. With recent titles including works by Samuel Beckett and Jean Genet, Olympia was known for publishing sexually frank but serious literature, and seemed (however briefly) like it might offer an appropriate home for Lolita and The Ginger Man.

From before he signed with Olympia, Nabokov suspected that his story of a nymphet and her tormentor might only find a home in Europe at a sketchy publishing enterprise. So when that suspicion turned into reality, Nabokov appears to have been less shocked than Donleavy to find his book included in the Traveller’s Companion series that would eventually encompass Tender Was My Flesh, White Thighs, and Until She Screams. Donleavy told the Guardian in 2004 that

“When I discovered that the novel was published in this pornographic series, I realised I would never have any reputation, that the book would never exist in any real form – it was just a piece of pornography. It wouldn’t get any reviews. It was a total nightmare.”

He says he vowed revenge on Girodias once he discovered the fate of his book, swearing that “if it were the last thing I ever did, I would redeem and avenge this work”.

As Girodias alternated posing as a high-minded litterateur with frank identification as a pornographer, Nabokov likewise began to take against him. His distaste only intensified after Lolita began drawing international attention and Girodias demanded staggering percentages in exchange for overseas rights to the book, threatening to distribute it in America himself. Nabokov began to look for ways to exit his deal with Olympia, twice wishfully declaring his contract void. He would end up in litigation that continued more than a decade after Lolita’s publication, when a French court finally closed the book on legal obligations between Nabokov and Olympia.

Donleavy’s struggle with Girodias would continue for longer. As the Guardian describes it, after more than two decades of legal battles, in which the proceeds from The Ginger Man likely helped fund both parties to the suit, Girodias tried to buy back the name Olympia Press at a bankruptcy auction. Donleavy sent his then-wife Mary to France, where she made the final bid and ended up purchasing the Olympia name for Donleavy, taking it forever from the man he felt had misrepresented his book from the beginning.

Donleavy’s struggle with Girodias would continue for longer. As the Guardian describes it, after more than two decades of legal battles, in which the proceeds from The Ginger Man likely helped fund both parties to the suit, Girodias tried to buy back the name Olympia Press at a bankruptcy auction. Donleavy sent his then-wife Mary to France, where she made the final bid and ended up purchasing the Olympia name for Donleavy, taking it forever from the man he felt had misrepresented his book from the beginning.

In his Lectures on Literature, Nabokov wrote that “great novels are great fairy tales.” Nabokov had also thought a good deal about fairy tales themselves, building subtexts incorporating their darker incarnations into his novels, from “Cinderella” in Pnin to “Der Erlkönig” in Pale Fire. And while music seems primarily to have been an irritant to him, Nabokov might well have appreciated the spirit of “Fairytale,” a song that withholds easy sentiment while acknowledging how close love and resentment sit to each other.

In the end, Donleavy and Nabokov each probably owe Maurice Girodias a debt of gratitude for taking a chance on their breakthrough novels—but Girodias also inspired a more-than-justified revenge from both men. It’s a kind of Nabokovian happily ever after, one rooted in payback and destitution. Not unlike the Pogues song, which—as with Nabokov’s best works—also has a hint “of malice at the back of [its] voice,” a streak of uncertainty, and joy.

Happy holidays.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Oct 31 2013

Filed In: News

Long after I expected the well of reviews for The Secret History to have run dry, two new appraisals popped up.

Earlier this month, Jeffrey Meyers weighed in on the book for The New Criterion. In “Legacy of Sorrows,” Meyers—a biographer of Edmund Wilson and many other literary figures—declares that

The magician buried his past in his art and Pitzer has exhumed it. She reads the novels for their cryptic hints, oblique allusions and hidden political themes, their cunning fusion of history and art, and reveals new dimensions of meaning.

Meyers lists many of the high points of the book, pointing to my emphasis on a reading of Lolita that more directly reflects Nabokov’s savage century and suggesting that the phrase “secret history” in the title is apt. (The full but paywalled review is here.)

Most critics looking at The Secret History have focused on that Lolita material, which is hardly a surprise, given the novel’s place in our literary firmament. But another October review, posted on The Daily Beast, tackles Pale Fire and its historical context—what I would call the heart of the book.

In “Pale Fire and the Cold War: Redefining Vladimir Nabokov’s Masterpiece,” Michael Weiss bounces from a modern, delusional would-be Russian emperor to the novel’s backstory before writing that

Fifty years is long time to wait for a decryption device but one has been furnished by Andrea Pitzer, the author of the The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, not just one of the most beguiling literary biographies to come out in years but also a first-rate addition to the groaning shelf of Nabokov studies.

Weiss goes on to trace the ways in which Nabokov’s most experimental novel echoes Soviet atrocities and the political hijinks of Nabokov’s lifetime—particularly the Cold War era of the book’s composition. Adding his own tidbits from rereading the novel, Weiss seconds the book’s thesis that Nabokov folded the Gulag-centered legends of the real-world Nova Zembla into Pale Fire‘s fantasy kingdom, which has big implications for… well, read the review—or the book—for yourself.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jul 29 2013

Filed In: Beginner

If you could afford to live anywhere in the world, where would you settle?

After the blazing success of Lolita in America and the sale of its movie rights to James Harris and Stanley Kubrick, Vladimir Nabokov and his wife Véra ended up in Switzerland, joining the community of celebrities at the Montreux Palace Hotel on the shores of Lake Geneva. Signing a lease in the summer of 1961, they took up residence there that October during the last months of Nabokov’s work on Pale Fire. The hotel remained Nabokov’s home for the rest of his life.

I traveled to Montreux in April 2011, spending one night at the Palace Hotel before moving to a less extravagant location a few blocks down the street. Before my arrival, I had asked for a tour of the place and historical information–the staff somehow thought I was doing a travel piece. (Accidental discovery/pro-tip: toss out enough questions in advance, and you might find yourself given a much nicer room than you paid for.)

Here’s a 180-degree view of the Montreux Palace and its surroundings, taken on shaky-cam from the front lawn, which sits between the hotel and the lake. Nabokov started out living on the third floor of the right-hand wing of the hotel, called Le Cynge (“the Swan”), where he could hear actor Peter Ustinov’s footsteps overhead as he worked. After a year the Nabokovs moved up to the top floor, which has a truly spectacular view–and no overhead neighbors.

You can see the Alps rising behind the hotel, and as the video pans around, the lake and the mountains again, home to the butterflies Nabokov loved to chase and collect.

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jul 22 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

Heroes returning home in disguise have been around since the days of Homer. For just as long, these heroes have been recognized despite their masks. Coming back from the Trojan War dressed as a beggar, Odysseus found that his dog and childhood nurse could see through his deception.

But what about events that transform survivors beyond recognition?

The collapse of recognition runs through both fiction and nonfiction about prisoners returning from the Soviet Gulag. Zeks released in the 1950s after years of being mangled by a state determined to reshape society found themselves unknown and unknowable. Russians left behind at home, who might once have understood the prisoners, had also been transformed in the meantime—often through complicity required to survive the system.

At the heart of The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov is the idea that Pale Fire‘s delusional narrator, who imagines himself the exiled king of Zembla, has a story and a past bound up deeply with the Gulag. But even absent the history explored in the book, Pale Fire parallels Gulag memoirs in multiple ways, sharing themes of ghostliness, shattered recognition, impostors, and fantastic stories of escape.

Recognition obliterated

In Journey Into the Whirlwind, Evgenia Ginzburg’s memoir of an eighteen-year Gulag sentence and exile, a mother mistakes her living son for her dead one. Equally estranged from herself, at one point in a labor camp, she recognizes her reflection only by its resemblance to her mother.

Vasily Grossman’s Forever Flowing recounts the return of Ivan Grigoryevich after thirty years in prison to find that his remaining family sees him as an “alien, spiteful, hostile” presence. They want to reunite with him but fear his judgment against them for compromises they have made. In a beautifully inelegant passage, they tell Ivan Grigoryevich what happened to his fiancée, whom he mourned for dead in the camps:

“Did she write you?”

“My last letter from her was eighteen years ago.”

“Yes, yes. She is married. Her husband is a chemical physicist, you know, engaged in all that nuclear business. They live in Leningrad—can you imagine it?—in the very same apartment where she used to live with her family. We usually run into her on vacation, in the fall. She always used to ask about you, but since the war, to tell the truth, she has stopped.”

Ivan Grigoryevich goes back to Leningrad and stands beneath his former lover’s window, but feels farther from her than he did when barbed wire separated them. In a place where those who vanished come back to haunt the living and are themselves haunted in return, it can be hard to know which characters are ghosts.

In “A Parable of Misrecognition” (paid) from The Russian Review, Alexander Etkind brings together the work of Ginzburg and Grossman to show how obliterating recognition revealed the horror of the camps and the distance between the prisoners and those who remained at home. He also makes an odd couple out of Freud and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in order to explain the ghostliness of Gulag returnees as a kind of doubled repression:

In 1956, Nikita Khrushchev used the concept of “unjustified repressions” as the euphemism for mass murders, arrests, and deportations. Millions of the surviving victims of these “repressions” were coming back to their homes after years or decades of separation from their families. In Sigmund Freud’s famous definition of 1919, “something which is secretly familiar, which has undergone repression and then returned from it,” was the uncanny. The two readings of the term “repression(s),” Freud’s and Khrushchev’s, are intimately correlated. When the repressed returned, these long-mourned, secretly familiar, inadvertently forgotten people were perceived as the uncanny.

Pale Fire and recognition

Charles Kinbote, the mad narrator of Nabokov’s 1962 novel Pale Fire, tells stories of a revolution that resulted in a totalitarian state. He is imprisoned but through spectacular, unbelievable means, escapes and makes his way to the West. By the time the book opens, he has lost his identity and has become unrecognizable even to himself, taking refuge in the delusion that he is the exiled king of the land of Zembla.

Notions of repression and the uncanny pervade Pale Fire—Kinbote believes locked doors become unlocked overnight, that someone has tied a white silk bow on the cat while he lay sleepless in his rented house. He hears approaching footsteps and calls the police, who find nothing amiss. Read more ›

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jul 12 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

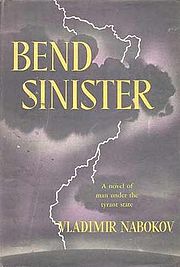

Stuck in the shadows of more accomplished, more loved siblings, lesser novels are often the bitter children of genius. They surrender family secrets and the details of their creators’ flawed parenting. Their failures provide their own intrigue.

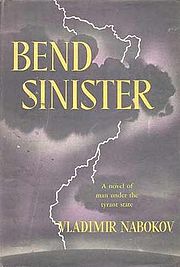

Such is the case with Bend Sinister, Vladimir Nabokov’s first novel written after his 1940 arrival in America. Revealing more authorial struggles than triumphs, the novel recounts the fate of a freethinking philosopher in a totalitarian state. Filled with echoes of “Lenin’s speeches, and a chunk of the Soviet constitution, and gobs of Nazist pseudo-efficiency,” the book lurches from horror to slapstick and back, grinding gears as it goes.

Such is the case with Bend Sinister, Vladimir Nabokov’s first novel written after his 1940 arrival in America. Revealing more authorial struggles than triumphs, the novel recounts the fate of a freethinking philosopher in a totalitarian state. Filled with echoes of “Lenin’s speeches, and a chunk of the Soviet constitution, and gobs of Nazist pseudo-efficiency,” the book lurches from horror to slapstick and back, grinding gears as it goes.

A chapter at the center of the story records a translator’s struggles with a state-sponsored, monstrous version of Hamlet. In his June 1960 review of the novel for Encounter, Frank Kermode criticized the Hamlet episode as a “digression” and “a useless but agreeable exercise of intellect.” The polyglot gamesmanship of the chapter fails to integrate the warped play into the stillborn society.

Yet the fate of Hamlet in a police state was not some abstract question, and the play’s the thing that links Nabokov’s fictional universe with our world in a haunting way. Just before Nabokov began work on his novel in 1941, Joseph Stalin criticized Hamlet, triggering its disappearance from Soviet stages for more than a decade. During this silence, Bend Sinister carried the wreckage of the play, standing as a condemnation of art stripped down to politics. In the process, Nabokov’s book indirectly memorialized a titan of Russian theater.

Hamlet in Russia

Shakespeare ranked as one of Nabokov’s three favorite writers (the others: himself and Pushkin), and the Bard’s plays make an appearance in more than one book by Nabokov, including the novel Pale Fire, whose title was provided by Timon of Athens and perhaps even by Hamlet itself. From the nineteenth century through the twentieth, Russians loved Shakespeare. Analyzed by the revolutionary Decembrists, the historical tragedies played a pivotal role in Alexander Pushkin’s ascent to literary immortality. As Siggy Frank notes, Nabokov particularly revered “the prodigious beauty” of Hamlet, calling it “probably the greatest miracle in all of literature.”

Constantin Stanislavsky and Gordon Craig staged a landmark Russian production of that play beginning in 1911. Their collaboration for the Moscow Art Theater revolutionized drama across Europe, inspiring veteran director Vsevolod Meyerhold—already a legend for his work in theater, opera, and cinema—to likewise try his hand at staging Hamlet.

Meyerhold’s first attempts began as early as 1915 but did not bear fruit. Pressured to alter his work under Tsarist rule, he cheered the Revolution and joined the Communists, dreaming that the arts might flourish under Soviet rule. But he soon found himself criticized on the pages of Pravda by revolutionary leader Nadezhda Krupskaya, wife of Vladimir Lenin.

Meyerhold’s first attempts began as early as 1915 but did not bear fruit. Pressured to alter his work under Tsarist rule, he cheered the Revolution and joined the Communists, dreaming that the arts might flourish under Soviet rule. But he soon found himself criticized on the pages of Pravda by revolutionary leader Nadezhda Krupskaya, wife of Vladimir Lenin.

He was eventually relieved of his position and chastised for “excessive radicalism.” As the decade wore on, he continued to struggle with Hamlet. He did not want to cut a line but could not find a way to leave it intact and stage it to his standards.

After Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin rose to power. Meyerhold’s reputation continued to grow, and despite the censors, he managed to carry out extraordinary work, including productions of Chekhov and Tchaikovsky. But still there was no Hamlet. Read more ›

Tags: Alexander Pushkin, Bend Sinister, Constantin Stanislavsky, Frank Kermode, Gordon Craig, Hamlet, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Pale Fire, Timon of Athens, Vladimir Nabokov, Vsevolod Meyerhold, William Shakespeare

posted by Andrea Pitzer on Jun 19 2013

Filed In: Intermediate

“I wanted to be a famous spy.”—Humbert Humbert

Vladimir Nabokov disdained most novels as “topical trash” and sought to create something transcendent in his own fiction. Yet topics dominating this month’s news about Edward Snowden—government surveillance, political intrigue, and spying—are oddly timeless when it comes to looking at Nabokov’s world.

Vladimir Nabokov disdained most novels as “topical trash” and sought to create something transcendent in his own fiction. Yet topics dominating this month’s news about Edward Snowden—government surveillance, political intrigue, and spying—are oddly timeless when it comes to looking at Nabokov’s world.

Growing up in the twilight of Russian Empire, where his father was first imprisoned under the Tsar in 1908 and then arrested under Lenin in 1917, Nabokov was familiar with state-sponsored surveillance and informers from both ends of the political spectrum. In Speak, Memory, he notes the evening his father’s librarian discovered a Tsarist stooge in a back room eavesdropping on a meeting. After the Revolution a family retainer led Soviet sympathizers to the hidden safe containing the Nabokov family jewels. And at the dawn of Russia’s civil war, Nabokov was himself captured in the hills above Yalta and interrogated on suspicion of signaling the British with his butterfly net.

After his father’s death in 1922 at the hands of reactionaries trying to assassinate someone else, Nabokov finished his university studies and then returned to Berlin. Through the Weimar era into the Nazi rise to power, the city remained a playground for double agents, with a reputation as the Soviet central bureau for espionage abroad.

During these years, Nabokov was said to make ill-advised jokes over the phone with a Jewish friend about when their (non-existent) Communist cell should meet. His short story “The Assistant Producer” tells a thinly veiled tale of Russian singer Nadezhda Plevitskaya, who went to prison for espionage and collaborating with her husband’s murderous intrigues. Nabokov’s novel Glory includes the drama of illicit border-crossings into Soviet Russia by anti-Bolshevik revolutionaries.

Early on, he developed a distaste for petty bureaucracy and laws that allowed “rat-whiskered consuls and policemen” to harass innocent refugees. He believed such thuggery could lead to the automated machinery of a police state in which massacres become “only an administrative detail.”

He would go on to write two novels that deal directly with totalitarian dystopias. In Bend Sinister, a bumbling group of informers and agents of the state try to enforce conformity. In Invitation to a Beheading, the state monitors and prosecutes corrupt thinking. In both, the protagonist faces execution.

Nabokov in America

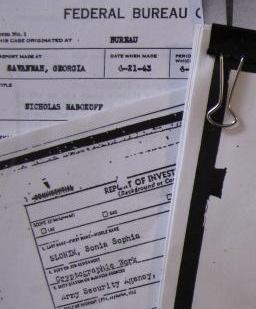

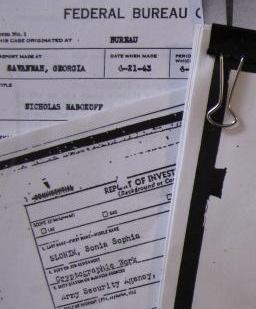

Even after Vladimir and Véra escaped to America in 1940, Nabokov’s brushes with intrigue and spying continued. Véra’s sister Sonia had been fraternizing with a known propagandist for the Nazis, and as she made her way from France to Casablanca to America, a telegram delivered to the U.S. Secretary of State warned Americans of French suspicions that she was a spy. Sonia was allowed to enter the country, but a “mail cover” was put on her correspondence—a pre-digital era metadata collection in which senders’ and recipients’ names were recorded without opening the mail itself. Read more ›

How does “Fairytale” connect with Nabokov? Donleavy leapt to prominence with The Ginger Man in 1955, the year Lolita was published. Nabokov invented a story of a European immigrant’s sexual depravity in America; Donleavy wrote of an American’s sexual adventures in Europe. Both authors steamrolled postwar obscenity standards and found their books’ distribution hamstrung by censorship. Both nevertheless went on to sell tens of millions of copies (The Ginger Man only slightly less than Lolita).

How does “Fairytale” connect with Nabokov? Donleavy leapt to prominence with The Ginger Man in 1955, the year Lolita was published. Nabokov invented a story of a European immigrant’s sexual depravity in America; Donleavy wrote of an American’s sexual adventures in Europe. Both authors steamrolled postwar obscenity standards and found their books’ distribution hamstrung by censorship. Both nevertheless went on to sell tens of millions of copies (The Ginger Man only slightly less than Lolita).  Donleavy’s struggle with Girodias would continue for longer. As the Guardian describes it, after more than two decades of legal battles, in which the proceeds from The Ginger Man likely helped fund both parties to the suit, Girodias tried to buy back the name Olympia Press at a bankruptcy auction. Donleavy sent his then-wife Mary to France, where she made the final bid and ended up purchasing the Olympia name for Donleavy, taking it forever from the man he felt had misrepresented his book from the beginning.

Donleavy’s struggle with Girodias would continue for longer. As the Guardian describes it, after more than two decades of legal battles, in which the proceeds from The Ginger Man likely helped fund both parties to the suit, Girodias tried to buy back the name Olympia Press at a bankruptcy auction. Donleavy sent his then-wife Mary to France, where she made the final bid and ended up purchasing the Olympia name for Donleavy, taking it forever from the man he felt had misrepresented his book from the beginning.